In recent times, the government has made public announcements about lost security papers used for printing title deeds, which raises the question: why place so much emphasis on a piece of paper that, in itself, may not serve as genuine evidence of ownership if it’s not well backed up with data? Consider the implications of a title deed for a multi-billion-shilling plot of land being identical in format to one worth only a few thousand shillings. The reality is that the title deed merely signifies initial proof of ownership, without bearing any reflection of the land’s value.

The focus, therefore, should not be on the physical document but on the data behind it. The true cornerstone of property rights lies in the history and integrity of ownership records—data that can be securely stored and accessed in digital form. Rather than issuing broad public warnings, the government could have taken more strategic action, such as blocking the affected title numbers within its land registry system. This would ensure that any searches would reflect the titles as void, much like a bank flags cheques for verification before payment is made.

This incident shines a light on a broader issue facing African governments: the persistent mistrust of technologies that they have invested billions to implement. We continue to rely on physical paperwork and traditional audits, even though these can be easily counterfeited. How many times have we seen fake receipts and documents printed on River Road, supplied by vendors operating out of briefcases? It is a stark reminder of the gap between the potential of modern technology and the reality of its adoption.

What is holding us back is not the lack of technological infrastructure, but the failure to fully trust and utilise it. As we grapple with issues of redundancy in outdated systems and overwhelmed institutions, we must recognise that the solution lies in innovation. Governments must embrace technologies such as blockchain for land registries, AI for governance, and automated systems to streamline processes and reduce human error. These tools are no longer futuristic—they are here and ready to be deployed.

I am proud to have been a member of the ICT Sector Working Group (SWG), where we rigorously examined the policies and regulations that govern our digital ecosystem. Through this work, we helped push forward recommendations that would not only safeguard the future but also enable the growth of a robust, technology-driven economy. And there is cause for optimism—our head of state is already championing the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into national strategy. This is a significant step forward, demonstrating that leadership is keen to position Kenya as a leader in the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

However, the journey has only just begun. As a nation, we must continue to demand best practices in ICT governance and innovation. We must push beyond the comfort zones of legacy systems and outdated approaches to governance. The institutions that fail to adapt, like Kenya Power and Posta, are already facing existential threats as alternatives—solar energy and digital communication—become more accessible. The same fate will befall other monopolistic institutions if they fail to embrace the winds of change.

The future belongs to nations that are bold enough to fully embrace digital transformation and trust the systems they build. It is time to step into that future.

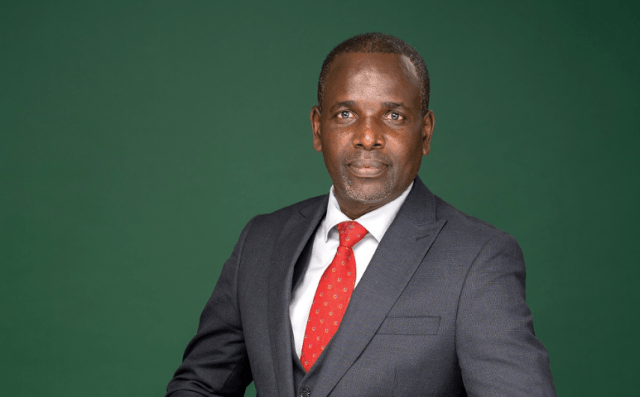

Edward Mwasi is a Media Industry Strategy and Innovation Consultant, CBIT.